Community Maritime Park

| | |

| Type | mixed-use public/private |

| Size | 27.5 acres |

| Facilities | multi-use stadium maritime museum education/conference center concert green |

| Operated by | Community Maritime Park Associates |

| Location | Trillium property |

The Vince Whibbs Sr. Community Maritime Park (often abbreviated to Community Maritime Park or CMP) is a public-private development that is planned to occupy the City-owned, 27.5-acre Trillium property. It will include a 3,200-seat "multi-use" stadium, a maritime museum, a conference/education center with University of West Florida classrooms, a variety of mixed-use development and a large public park along the waterfront.

The project was conceived and promoted by a group of prominent citizens including Admiral Jack Fetterman, businessman Quint Studer and UWF President John Cavanaugh. An initial layout was refined in public focus groups by urban planner Ray Gindroz, and the revised conceptual plan was approved by the Pensacola City Council in 2005. A grassroots ad hoc group called Save Our City attempted to overturn the council's decision and forced a special referendum, but the project was affirmed by city voters on September 5, 2006.

The park will be funded by a $40 million Community Redevelopment Agency bond and an estimated $30 million or more in private investment. Control and budget for the project is overseen by the non-profit Community Maritime Park Associates. The master developer is Utah-based Land Capital Group, which formed an ad hoc corporation, Maritime Park Development Partners (MPDP), to handle construction and development.

The park is named for former Mayor Vince Whibbs, who became a principal of the venture after the death of Admiral Fetterman before passing away himself during the referendum campaign.

Contents

History[edit]

Background[edit]

In 2000, the City of Pensacola purchased a 27.5-acre peninsular parcel of formerly industrial land, commonly known as the Trillium property, from The Trust for Public Land, a national nonprofit conservation organization that had acted as an intermediary in the complex transaction, for $3.63 million.[1] Located south of City Hall and Main Street to Pensacola Bay, and bounded to the east and west by Port Royal and Bruce Beach respectively, it was the largest undeveloped waterfront property in the Pensacola area.

The site was soon considered for a municipal auditorium to replace the aging Bayfront Auditorium. Architectural firm Bullock Tice Associates created a conceptual plan, called the Festival Park, which was approved by the Pensacola City Council on November 21, 2002. Initial work had already begun, including a massive concrete breakwater on the southern edge of the property, when a group called Citizens Against Trillium (led by Charles Fairchild) petitioned for a referendum on the project, utilizing a yet-untried proviso of the city's charter. On March 25, 2003 the citizens of Pensacola voted to overturn the council's decision and scrap the plan.

In late 2004, months after Hurricane Ivan devastated the Pensacola area, city officials including City Manager Tom Bonfield and Mayor John Fogg met informally with a group of business leaders to discuss ways to revitalize the battered city. Someone mentioned that Admiral Fetterman and Quint Studer had been seeking homes for their respective projects: a museum of maritime history, which Fetterman had earlier tried to attach to the Festival Park project,[2] and a new ballpark for the Pensacola Pelicans, which Studer had initially planned to build at the old American Creosote site.[3]

According to Mort O'Sullivan, who was at the initial meeting, "Fetterman and Studer had never discussed the combination idea with each other and neither was present at the meeting, but it was agreed we would seek the opinions of each."[4] After meeting with the two, architect Miller Caldwell agreed to produce a conceptual rendering. After seeing the drawings, Fetterman reportedly pushed his notes into the middle of the table and said, "Ladies and gentlemen, I'm all in."[4] The group then approached John Cavanaugh, who was seeking to expand UWF's presence downtown, and he suggested using the state university's umbrella to provide matching funds to the maritime museum.

- Renderings of the initial Caldwell Associates design

The Community Maritime Park Associates presented the plan to the Pensacola City Council on January 18, 2005 with more than 350 supporters in attendance, many wearing stickers with the slogan "Right Idea, Right Time." The plan was approved in concept by an 8-1 vote. Dissenting council member Marty Donovan said of the presentation, "Obviously, while we were working on hurricane recovery, another group came up with their plan, independent of we city leaders. My constituents read about it in the paper. And two days later, we were at a well-orchestrated pep rally."[5]

Festival Park opponent Charles Fairchild called the proposal "an interesting plan that has a lot for everyone,"[6] but requested that city staff conduct a public input process to refine the park's design. Urban planner Ray Gindroz, whose Pittsburgh-based Urban Design Associates helped create the CRA's historic district master plan in 2003, was invited back to host a series of public input sessions and focus groups. "This is one of the most exciting things I've seen," Gindroz said. "I'm very impressed with the generosity and the public-spirited nature of the people involved and the way they are handling this."[7] The Avery Group, led by Marty Donovan's brother Tim, donated its consulting services to the effort.[8]

After more than 50 presentations and 16 public input sessions, Gindroz unveiled the revised conceptual plan on April 7, 2005. Many of the details had been changed to reflect recommendations made by residents; for example, the office buildings and other structures, originally located near the bay, were moved to the northern edge along Main Street.[9] "I'm excited about this project," Gindroz said. "The waterfront now is about as dead as you can get and is separated from the rest of the city. … The intent is to make something unique for Pensacola that plays on its history."[10]

Shortly after the revised conceptual designs were released, the Pensacola News Journal published a viewpoint by Charles Fairchild that decried the plan as "a small open waterfront space that lacks easy access, has limited parking, and for the most part becomes a private enclave for those who have the good fortune of having their buildings and activities there."[11] Councilman Marty Donovan suggested issuing a nationwide request for proposals (RFP) for the Trillium property, but his motion was voted down 9-1 on June 9.[12] City Manager Tom Bonfield later defended defended the lack of a more thorough RFP process, saying the Community Maritime Park Associates were the only group to present a "timely and responsive" plan since the Festival Park proposal was overturned.[13]

On June 23, 2005, the council voted 9-1 (with Donovan again the lone dissenting vote) to move forward on the CMP proposal.[14]

- Revised conceptual designs by Ray Gindroz and Urban Design Associates

Referendum[edit]

On November 4, Marty Donovan released an open letter to Quint Studer and Charles Fairchild calling for a referendum on the maritime park project. Fairchild had started an opposition group called Save Our City that was already investigating the possibility. "I think the referendum would kind of get it over with," he said. "The longer this thing waits and festers, the worse it's going to be."[15]

Mayor John Fogg expressed disapproval for the idea, calling it "government by referendum." Studer concurred: "You can't just keep waiting for one more thing, another meeting, another study, another vote. Because every day when we don't move forward on our projects, we lose more of our young people."[15]

CMP principal Admiral Jack Fetterman died on March 24, 2006, after months of declining health.[16] Just days later, on March 27, the City Council voted 9-1 to approve the master lease agreement for the project. Save Our City kicked off a petition campaign to force a referendum the same day.[17] Mayor Emeritus Vince Whibbs, a vocal proponent of the project, was selected on May 12 to succeed Fetterman as the third principal of the Community Maritime Park Associates,[18] but himself passed away on May 30.[19] The City Council later voted to name the park in his honor.[20]

On May 24, Save Our City submitted more than 9,000 signed petitions to the city, which forwarded them to Escambia County Supervisor of Elections David Stafford for verification.[21] A minimum of 5,600 valid signatures were needed, and Stafford's office completed verification of 7,122 signatures on June 13, ensuring a referendum would take place.[22] The issue was placed on the September 5 ballot, along with the state primary races and a renewal of the half-cent school tax.

In the remaining months before the referendum, both sides — Save Our City and a pro-park group called Friends of the Waterfront Park — engaged in a hard-hitting campaign that often resorted to personal attacks and accusations. The Friends political group, funded largely by Quint Studer, mounted a campaign portraying critics of the plan as curmudgeonly naysayers, embodied by a pair of cartoon characters named Chuckie and Donno.[23] Save Our City depicted Studer as a scheming carpetbagger who was getting a "$100 million ballpark" (a figure derived from the bond, interest and an estimated value of the property) for only $1 a year.[24]

Fairchild also produced a series of emails from marketing firm E. W. Bullock Associates, obtained through a public records request to university and city administrators, which he claimed showed an inappropriate back-room attempt "to push their plan on the council and the people of Pensacola" and represented a conflict of interest on the part of the firm, which frequently did work for the City of Pensacola.[25] In one email, dated January 19, 2005, public relations specialist Raad Cawthon offered a reading of the council members' predispositions and boasted of at least "five votes in our pocket."[25] However, both Bullock and the council insisted Cawthon was just "counting votes" and denied any impropriety: "No one from the maritime park has so much as bought me a Diet Coke," said Councilman P. C. Wu. "If I'm in their pocket, they got me very cheap."[3] Just days before the referendum, local activist Tom Garner filed a complaint with the state attorney's office, citing the emails as evidence of possible Sunshine Law violations.[26] The state attorney's office quickly dismissed the complaint, determining there were "insufficient facts to establish that any violation of the Sunshine Law occurred."[27][28]

In the end, the park project received endorsements by the Pensacola Bay Area Chamber of Commerce,[29] the Gulf Breeze Chamber of Commerce,[30] the UWF Board of Trustees,[31] media outlets including the Pensacola News Journal[32] and Independent News,[33] and a myriad of professional groups, businesses and prominent individuals. The Friends of the Waterfront Park spent nearly $600,000 to promote the project, most of it donated by Studer and his company, compared to the $68,700 raised by Save Our City.[34]

The Community Maritime Park was approved in special referendum on September 5, 2006, with around 56 percent of city voters approving both the conceptual plan and the $40 million public bond.[35] The official tally was 9,684 to 7,701.[36]

Development[edit]

Master developer selection[edit]

After an extended deadline, the two candidates for master developer submitted their RFP responses in late May 2008.

The proposal by Land Capital Group[37] only estimated the cost of public improvements, as private investors would be sought later, but included a letter of interest from Marriott International regarding a possible hotel on the property. The proposal also omitted a number of features, including the Great Lawn, formal gardens, lower west promenade, wharfs and piers, the lighthouse, dredging of the west marina, and the central parking structure, which they claimed could not be built with current funds: "Until this issue is resolved, the current plan is only conceptual." Nevertheless, the total cost of the revised project was estimated at $54 million — $16 million more than the remaining public funding. The group proposed seeking federal grants in combination with interest earnings and revenue bonds to make up the shortfall. Their timeline (using "best case assumptions") estimated project completion by December 2010.

The proposal by Trinity Weston Cypress[38] combined public and estimated private costs (which one city consultant called "confusing"[39]) for a total buildout cost in excess of $247 million. However, the budget for remediation and infrastructure alone totaled nearly $50 million, or about $12 million more than the remaining public money. The TWC timeline estimates several years of permitting and site work, with construction concluding in 2013.

The Land Capital proposal was selected by the CMPA Board on (date needed). After City Manager Al Coby and consultants took issue with several points in early drafts, the contract went through several months of revisions and negotiations. A final draft was approved by the Pensacola City Council's Committee of the Whole on April 20;[40] by the CMPA Board on April 21;[41] and by a unanimous vote of the full City Council on April 23.[42]

Construction begins[edit]

Two important environmental permits, one from the Florida Department of Environmental Protection and the second from the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, were received by the CMPA Board in February 2009.[43]

The official groundbreaking ceremony for the park took place on September 17, 2009.[44]

Features[edit]

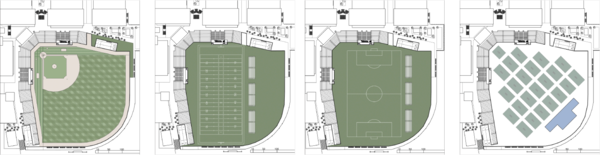

Multi-purpose stadium[edit]

One of the largest and most contentious elements of the Community Maritime Park is the multi-purpose stadium situated in the eastern-central portion of the property. It will become the home field of the Pensacola Pelicans, owned by CMP principal Quint Studer, who has pledged an annual lease of $170,000 for at least ten years to use the ballpark.[45] The stadium will also be designed to accommodate other uses, including soccer and football games and outdoor concerts.

Maritime museum[edit]

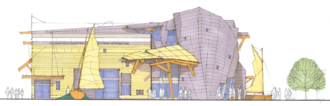

The western side of the property will feature the Admiral John H. Fetterman State of Florida Maritime Museum and Research Center. Conceived by the late Vice Admiral Jack Fetterman, for whom it was later named, the 50,000 square foot, $18 million museum was originally planned to be funded half by private donations and half by the State of Florida's Alec P. Courtelis Matching Gift Program.

The museum's interactive, educational displays will showcase artifacts from Pensacola's maritime history. The University of West Florida will operate active research facilities in the areas of public history, underwater archaeology, marine biology and environmental science.

- Renderings of the Fetterman Maritime Museum

Education/conference center[edit]

The University of West Florida will also host classes for its business and continuing education departments at the park. The same complex will also house a conference center, which Quint Studer has promised to use for his company's health care seminars. The university will contribute about $15 million for the center's construction and will pay an estimated $350,000 in annual rent for at least ten years.[46]

Mixed-use area[edit]

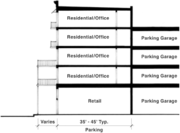

Several buildings will be constructed on the northern end of the property, between Main and Cedar Streets, to be leased to third parties for retail shops, restaurants and other uses. These leases are expected to generate a large portion of the park's revenue.

Public park space[edit]

Water garden & Spring Street park[edit]

South park & waterfront promenade[edit]

Plaza DeVilliers[edit]

Plaza DeVilliers will be a civic square located the terminus of the DeVilliers Street extension, adjacent to entrances of all the major attractions and serving as a central "meeting point" for park visitors. It will feature a paved plaza, information kiosk, and a grassy lawn landscaped with canopy trees.

DeVilliers Wharf[edit]

DeVilliers Wharf will be a public promenade running north-south along the western edge of the property as a pedestrian extension of De Villiers Street. It will be 55' wide and features a split-level design.

Other features[edit]

Parking[edit]

The final buildout of the park calls for two main off-street parking areas on the park property: a surface lot of approximately 70 spaces in the northwest corner and a four-story parking garage in the central mixed-use block, which will be "wrapped" by the five-story-tall commercial and residential structures, resulting in a total parking capacity of around 1,060 vehicles.[47] However, as the cost of the garage may not be possible in the scope of phase one, it may start as a surface lot of around 350 spaces.

Marina & fishing piers[edit]

Lighthouse[edit]

The master plan depicts a lighthouse in the southwest corner of the property, but this is not included in the scope of phase one.

Heritage museum[edit]

In addition to the park's eponymous maritime museum, other museum ideas have been proposed by various groups to occupy the property. In 2005, leaders of the Pensacola Sports Association (the headquarters of which are near the Trillium site on Main Street) expressed interest in adding a Sports Hall of Fame to the park project, showcasing the careers of famous Pensacola athletes like Jerry Pate, Emmitt Smith, Roy Jones and Justin Gatlin.[48]

Funding[edit]

CRA bond[edit]

Much of the park's public funding comes from a $40 million Community Redevelopment Agency (CRA) bond. The CRA is a tax increment financing district created to revitalize the city core. City and county taxes paid on property improvements since 1984 are deposited into the CRA fund and reinvested into the district through capital projects. Thus, a bond through the CRA is paid by property owners within the district, but does not require any new taxes.

At the time of the park proposal, the CRA had an annual revenue of $3.4 million and was growing at a rate of 20 percent a year. City Manager Tom Bonfield used more conservative estimates in considering a CRA bond, assuming zero growth in the 2006 fiscal year, and announced to the council that "there is a way for the project to be financially feasible."[49] According to Bonfield, the final cost with interest over the life of the bond would be $77 million. "There is a cost, there's no hiding that," he said. "But that's the way public projects are done."[49]

Strand decision[edit]

In 2006, Pensacola veterinarian Greg Strand filed a lawsuit challenging the Southwest Escambia Improvement District, which proposed to use tax-increment financing (TIF) issue $135 million in bonds for the widening of Perdido Key Drive. Strand argued that the bonds were unconstitutional because they obligated the citizens within the district to long-term debt without their direct approval by referendum. In 2007 the Florida Supreme Court sided with Strand, overturning decades of precedent and endangering TIF-funded projects throughout the state. Even though the CMP project had been approved in a referendum by voters in the city, which includes the entirety of the CRA district, City Attorney John Fleming indicated that a county-wide referendum may be needed. Backers of the park project began looking for new ways to finance the $40 million bond.

However, on September 18, 2008, the Supreme Court reversed their earlier decision, allowing the project to move forward with CRA bonds.[50]

Other public money[edit]

Much of the park funding will also come from other public sources. The $18 million maritime museum will receive up to half of its construction costs from the State of Florida's Alec P. Courtelis Matching Gift Program. Operating costs for the museum and research center will be paid by the state-funded University of West Florida, in addition to at least $350,000 in annual rent for the education/conference center.[46]

The master developer, Maritime Park Development Partners, is also pursuing millions of dollars in federal grants from the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009.

Private donations & investments[edit]

Quint Studer has made a number of financial commitments to the Community Maritime Park. He has pledged for the Pelicans to play at the park for a minimum of ten years, paying an annual lease of at least $175,000. He has also agreed to pay $250,000 a year for five years to cover any initial operating deficit; if there is no such deficit, the money will be donated to local charities.[51]

Pensacolian Randall K. "Skip" Hunter and his wife Martha donated $1 million to the UWF Foundation for the construction of an amphitheater on the waterfront lawn and to help fund development of the maritime museum. The concert shell will be designated the Randall K. and Martha A. Hunter Amphitheater in their honor by the university.[52]

Rising costs & development "phases"[edit]

When urban planner Ray Gindroz revised the initial park design, he was not asked to stay within a budget. As a result, according to Tom Bonfield, he "added a whole bunch of stuff that wasn't there before"[53] — amenities like a lighthouse, a concert shell, and a large-scale replica of the William Panton Mansion. Combined with an estimated 12.5 percent increase in construction costs after Hurricanes Katrina and Rita,[54] and park developers began contemplating multiple "phases" of construction that would deliver all the promised features while not exceeding the $40 million public bond.

When Land Capital entered into final negotiations to serve as master developer, it was revealed that their proposal to develop the public portion of the park totaled more than $50 million, exceeding the $40 million bond allotted for those improvements. Land Capital president Scott Davison was confident that $12 million or more would be available through federal grants, but indicated that the alternative would be to include the UWF classrooms or conference center in a portion of the private improvements or postpone construction of those elements until funds were available.[55]

Economic impact[edit]

In February 2005, the Haas Center for Business Research and Economic Development released a study that projected about $51 million a year in new economic activity from the park, including about 767 new jobs and $24.1 million in labor income a year. The center also estimated an additional $124 million in initial development and construct impact, along with 1,694 jobs and $51 million in labor income.[56] Former finance professor and park critic C. C. Elebash has claimed the economic impact will be closer to $39 million.[45]

Ownership & administration[edit]

The Community Maritime Park will be administered by the non-profit Community Maritime Park Associates (CMPA), which will be responsible for the development, operation and maintenance of the park. The City of Pensacola retains ownership of the property, which it will lease to the CMPA for 60 years at $1 a year (a figure often used in accounting to represent a transfer of control). All net revenue received from leases will be deposited back into the city's budget, and the city will own all buildings and other improvements located on the property after the lease expires.

External links, references & notes[edit]

- City of Pensacola

- Friends of the Pensacola Bay Area's Vince J. Whibbs Sr. Community Maritime Park – Official volunteer group

- ↑ "City OKs contract to buy Trillium site." Pensacola News Journal, March 29, 2000.

- ↑ John H. Fetterman. "Viewpoint: Opportunity here, now for a Maritime Museum." Pensacola News Journal, January 26, 2003.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Michael Stewart. "Officials deny wrongdoing." Pensacola News Journal, June 24, 2006.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Michael Stewart. "A city divided." Pensacola News Journal, August 20, 2006.

- ↑ Sheila Ingram. "Revote on park plan invites critics." Pensacola News Journal, January 21, 2005.

- ↑ Sheila Ingram. "Park is talk of the town." Pensacola News Journal, January 19, 2005.

- ↑ Sheila Ingram. "Bayfront planners welcome options." Pensacola News Journal, January 23, 2005.

- ↑ Sheila Ingram. "Float ideas about waterfront park plan." Pensacola News Journal, February 14, 2005.

- ↑ Sheila Ingram. "Maritime park details take shape." Pensacola News Journal, March 16, 2005.

- ↑ Sheila Ingram. "Gindroz unveils final park plans." Pensacola News Journal, April 8, 2005.

- ↑ Charles Fairchild. "Viewpoint: Maritime park plan falls way short of needs." Pensacola News Journal, May 17, 2005.

- ↑ Brett Norman. "Sides spar over park proposal." Pensacola News Journal, June 10, 2005.

- ↑ Carlton Proctor. "Park opponents blast plan." Pensacola News Journal, September 13, 2005.

- ↑ Sheila Ingram. "Maritime park step closer to reality." Pensacola News Journal, June 24, 2005.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Brett Norman. "Donovan proposes referendum for park." Pensacola News Journal, November 5, 2005.

- ↑ Troy Moon and Lesley Conn. "'Gentle warrior' passes." Pensacola News Journal, March 25, 2006.

- ↑ Alvin Peabody. "Council passes park plan." Pensacola News Journal, March 28, 2006.

- ↑ Alvin Peabody. "Whibbs to join park project's board." Pensacola News Journal, May 13, 2006.

- ↑ Troy Moon. "Champion of city passes." Pensacola News Journal, May 31, 2006.

- ↑ Alvin Peabody. "Proposed maritime park named after late Mayor Emeritus Whibbs." Pensacola News Journal, August 25, 2006.

- ↑ Alvin Peabody. "Park vote moves closer." Pensacola News Journal, June 8, 2006.

- ↑ Alvin Peabody. "City Council schedules vote on downtown park proposal." June 23, 2006.

- ↑ Wayne A. Stewart. "Letter to the Editor: Insulting cartoon." Pensacola News Journal, August 5, 2006.

- ↑ Michael Stewart. "Project opponents say funds from CRA would serve better purpose elsewhere." Pensacola News Journal, August 20, 2006.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 Michael Stewart. "Opponent of park cries foul." Pensacola News Journal, June 23, 2006.

- ↑ Michael Stewart. "Activist files park complaint." Pensacola News Journal, August 30, 2006.

- ↑ Michael Stewart. "Office dismisses park plan complaint." Pensacola News Journal, September 2, 2006.

- ↑ State Attorney's response to Garner complaint

- ↑ "Pensacola Chamber endorsing project." Pensacola News Journal, August 22, 2006.

- ↑ Sean Dugas. "Park friends, foes plan last-minute events." Pensacola News Journal, August 25, 2006.

- ↑ Sheila Ingram. "Votes, grants, endorsements propel park plan." Pensacola News Journal, June 25, 2006.

- ↑ "Our view: Voters should approve Maritime Park." Pensacola News Journal, August 27, 2006.

- ↑ Rick Outzen. "If undecided on the Waterfront Park." Rick's Blog, September 5, 2006.

- ↑ Mark O'Brien. "Money, young people help bring a new look to Pensacola politics." Pensacola News Journal, September 6, 2006.

- ↑ Michael Stewart. "Voters OK park." September 6, 2006.

- ↑ Election results

- ↑ Land Capital Group response

- ↑ Trinity Capital response parts a, b, c & d

- ↑ "Maritime troubles mount." Pensacola News Journal, June 8, 2008.

- ↑ Kris Wernowsky. "Park clears big hurdle." Pensacola News Journal, April 21, 2009.

- ↑ Kris Wernowsky. "Park deal OK'd." Pensacola News Journal, April 22, 2009.

- ↑ Thyrie Bland. "Council sparks park." Pensacola News Journal, April 24, 2009.

- ↑ "Maritime Park receives final environmental permit." Pensacola News Journal, February 25, 2009.

- ↑ Thyrie Bland. "Maritime Park work begins today." Pensacola News Journal, September 18, 2009.

- ↑ 45.0 45.1 Carlton Proctor. "Park plans revised amid higher costs." Pensacola News Journal, October 17, 2005.

- ↑ 46.0 46.1 Alvin Peabody. "Cavanaugh boosts UWF center." Pensacola News Journal, March 7, 2006.

- ↑ Note: The design guidelines alternately describe an eight-story garage in the central block, including one level below grade, that would allow a total capacity of "no less than 2,000 spaces."

- ↑ Shelley Robinson. "A park for the stars." Pensacola News Journal, April 10, 2005.

- ↑ 49.0 49.1 Sheila Ingram. "Council to review park plan." Pensacola News Journal, March 7, 2005.

- ↑ "Decision puts park on track." Pensacola News Journal, September 19, 2008.

- ↑ Lesley Conn. "Maritime park vote on horizon." Pensacola News Journal, March 3, 2006.

- ↑ Jamie Page. "Public has say on park." Pensacola News Journal, December 13, 2008.

- ↑ Sheila Ingram. "Park faces more scrutiny." Pensacola News Journal, June 20, 2005.

- ↑ "Sample of projects battling a rise in costs." Pensacola News Journal, October 16, 2005.

- ↑ Jamie Page. "Funds build less at park." Pensacola News Journal, December 6, 2008.

- ↑ Sheila Ingram. "Park plan praised." Pensacola News Journal, March 20, 2005.