Civil War

Pensacola and the surrounding area was home to several key clashes in the early stages of the American Civil War. The Confederate Secretary of the Navy, Stephen Mallory, was a Pensacolian and is buried in historic Saint Michael's Cemetery.

Contents

First hostilities[edit]

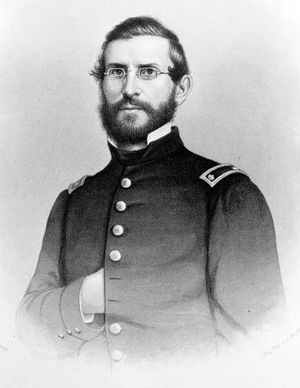

In January 1861, the United States Army forces in Pensacola consisted of Company G, 1st United States Artillery, which was stationed at Barrancas Barracks, near Fort Barrancas. The company's commanding officer, Captain John H. Winder, as well as his executive officer, First Lieutenant A. R. Eddy, were absent on leave, which left only two relatively inexperienced Army officers in Pensacola: First Lieutenant Adam J. Slemmer commanding, and Second Lieutenant Jeremiah H. Gilman.[1]

South Carolina became the first state to secede from the union on December 20, 1860. On January 8, 1861, a small group of men attached to Colonel William H. Chase's command approached Fort Barrancas but were repelled by gunfire.[2] Lt. Gilman, second in command at Pensacola, recounts the scene:

| About midnight a party of twenty men came to the fort, evidently with the intention of taking possession, expecting to find it unoccupied as usual. Being challenged and not answering nor halting when ordered, the party was fired upon by the guard and ran in the direction of Warrington, their footsteps resounding on the plank walk as the long roll ceased and our company started for the fort at double-quick. This, I believe, was the first gun in the war fired on our side. | ||

—Lieutenant J. H. Gilman, "With Slemmer in Pensacola Harbor."[1] | ||

On January 10, Florida became the third state to secede. In February the seceding states would form the Confederate States of America. Shortly after Florida's secession, Lieutenant Slemmer decided to abandon Forts Barrancas and McRee and consolidate Union forces at Fort Pickens. Slemmer explained his decision as strategically necessary:

| I called on Commodore [James] Armstrong (Union Commanding Officer of the Navy Yard) ... He had received orders to cooperate with me. We decided that with our limited means of defense we could hold but one fort, and that should be Fort Pickens, as it commanded completely the harbor and the forts and also the navy yard. | ||

—"Pensacola in the Civil War." Florida Historical Quarterly, Vol. IX, No. 2, 1978. | ||

Slemmer's men destroyed over 20,000 pounds of gunpowder at Fort McRee, spiked the guns at Fort Barrancas, and evacuated 51 soldiers and 30 sailors to Fort Pickens.[3] On January 12, rebel troops from Alabama and Florida occupied the Navy Yard and Forts Barrancas and McRee; William Conway famously refused to strike the Union colors. The two Union naval ships in the harbor, Wyandotte and Supply, were commanded by officers loyal to the Union and did not fall into rebel hands.

Chase presses for surrender[edit]

On the evening of January, Colonel William H. Chase of the Florida state troops sent a party of four men to Fort Pickens, who "demanded a peaceable surrender of [the] fort." The party was turned away.

On January 15, Chase himself came to Fort Pickens, accompanied by Captain Farrand, previously of the Union Navy. Lt. Gilman recounts a portion of the exchange between Chase and Slemmer:

I took the paper and read aloud the demand for the surrender. As soon as I finished, I handed the paper to Lieutenant Slemmer, when he and I went a few paces away; and, after talking the matter over, it was decided, in order to gain time and give our men a night's rest, to ask until next day to consider the matter. We returned to Colonel Chase, and the following conversation took place:

The next day the reply, refusing to surrender, was sent, Captain Berryman of the Wyandotte taking it to the yard. |

||

—Lieutenant J. H. Gilman, "With Slemmer in Pensacola Harbor."[1] | ||

Chase demanded surrender once more, by letter, on January 18, at which point Slemmer again declined. Fort Pickens would remain in Union control for the duration of the war.

Reinforcements[edit]

In the early months of 1861, while James Buchanan was still President, Stephen Mallory had negotiated a gentleman's agreement that stipulated the Union would not reinforce Fort Pickens as long as rebel troops did not attempt to take it. However, incoming president Abraham Lincoln did not intend to honor the agreement, and on March 12 ordered troops about the USS Brooklyn to land at Fort Pickens. The orders reached the Brooklyn on March 31, and on April 12 the troops successfully reinforced the fort.[2] Additional troops were landed from the USS Atlantic on April 16.[3]

On March 11, 1861, Confederate general Braxton Bragg arrived in Pensacola and assumed command of the troops present. On April 19, Bragg declared martial law in Pensacola.[3] On October 22, the Confederate troops under General Bragg's command at Pensacola were organized as the Army of Pensacola.[4]

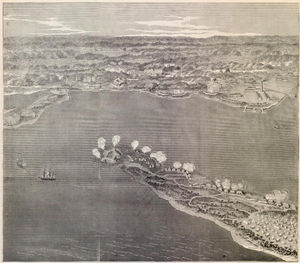

Battle of Santa Rosa Island[edit]

In September 1861, a schooner called the William H. Judah, of which the Confederacy had contracted the use, ran the Union blockade and successfully entered Pensacola's harbor, docking at the navy yard. When it became apparent to Union forces that the Confederacy was attempting to outfit the Judah as a privateer, they developed a plan to sabotage the work. In the early morning hours of September 14, a Federal raiding party of about 100 sailors and marines in four small boats cast off from the USS Colorado bound for the Judah. Approaching the vessel at around 3:30 AM, they were greeted with musket fire from Confederate guards; however, the raiding party successfully boarded the Judah and set it aflame. The raiding party also managed to spike a gun battery at the navy yard before retreating. The small clash resulted in three deaths apiece on both sides, the first of the war in Florida, as well as several wounded.[3][5]

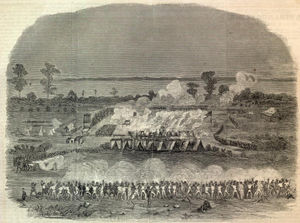

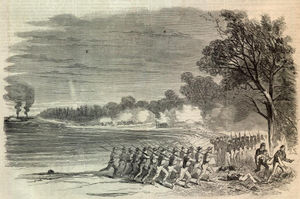

In response to the attack on the Judah, Confederate general Braxton Bragg ordered an attack on Fort Pickens. A force of over 1,000 men under general Richard H. Anderson set out from Pensacola on the evening of October 8, landing on Santa Rosa Island about four miles east of Fort Pickens. From there the Confederate troops were divided into three groups: one which travelled on the north (Sound) side of the island, one which travelled on the south (Gulf) side, and a third which trvalled just behind both, used as a flank to connect the groups. After marching for three miles, the Confederate troops were spotted by an encampment of the 6th New York Volunteer Infantry and fired upon. However, the Confederate troops had the element of surprise and quickly overwhelmed the encampment, sending the 6th New York retreating back to Fort Pickens. Soon after, though, the Confederate general Anderson decided to retreat, during which Union forces pursued and caused extensive casualties. The retreat is described in the Florida Historical Quarterly article, "Pensacola in the Civil War":

| As dawn was rapidly approaching, and the fort and batteries were alerted to his assault, [Anderson] abandoned his plans for any further attack and ordered his troops to march back to their original point of debarkation.

In their hasty retreat, the Southerners found themselves being outflanked. As they were boarding the steamers, flats, and barges, the well trained Union infantry took careful aim from behind the closest dune ridge and showered the Confederates with large quantities of effective musketry that caused considerable death and injury. Florida's first major land battle ended when the steamers left the island for Pensacola. The Confederates reported a loss of 18 dead, 39 wounded and 30 missing or presumed prisoners of war. [Union commander] Colonel Brown stated his losses as 14 dead, 29 wounded and 24 prisoners. |

||

—"Pensacola in the Civil War." Florida Historical Quarterly, Vol. IX, No. 2, 1978. | ||

Artillery exchanges[edit]

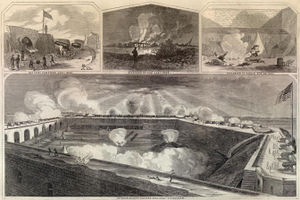

A series of artillery battles took place during late 1861 and early 1862, in which the Union guns generally prevailed, causing substantial damage to Confederate fortifications.

At 10:00 AM on the morning of November 22, the Union batteries at Fort Pickens opened fire on the Confederate steamers docked at the Navy Yard wharf. The steamers escaped the line of fire with minimal damage, but the Confederate guns returned fire. The Union ships USS Richmond and USS Niagara soon moved closer to shore and joined the Union barrage, firing primarily at Fort McRee. Union guns shot off the flagstaffs at both McRee and Fort Barrancas. Confederate general Braxton Bragg called the artillery battle "grand and sublime," and wrote that "the houses in Pensacola, ten miles off, trembled from the effect; and immense quantities of dead fish floated on the surface of the lagoon, stunned by the concussion."[6]

The artillery battle continued the next day. In all, Union troops expended 5,000 rounds of ammunition while Confederate troops returned some 1,000 shots. Fort Pickens on the Union side sustained little damage, but Confederate-held Fort McRee, its water battery, as well as the navy yard and the village of Warrington all sustained extensive damage. Federal troops did sustain two deaths and 13 wounded. Federal artillery inflicted even more damage on January 1 and 2, 1862, causing extensive fire damage at the Navy Yard and exploding the powder magazine at Fort McRee.[3]

Pensacola surrenders[edit]

The Union invasion of Tennessee in early 1862 necessitated Confederate reinforcement and on March 19 around 8,000 Confederate troops left Pensacola for Tennessee, leaving behind only a token force. Confederate Colonel Thomas M. Jones was left in command at Pensacola and authorized to use his own discretion concerning the evacuation of the city. Upon learning on May 7 that Union commander David Farragut's fleet was anchored off Mobile Bay, Colonel Jones quickly removed most of the Confederate artillery and supplies from Pensacola. The last Confederate troops to leave, on May 9, set fire to the remnants of the Navy Yard and other Confederate defenses. Most Pensacola residents evacuated inland to Greenville, Alabama.[6][3]

Pensacola, left in the hands of acting Mayor John Brosnaham, surrendered to U.S. troops under Lieutenant Richard Jackson on May 10. That evening, Union troops raised the stars and stripes over Plaza Ferdinand VII.[3]

Union naval officer David Dixon Porter recounted the surrender in his Incidents and Anecdotes of the Civil War:

| The gentleman in question was attired without regard to expense. He wore a blue coat with brass buttons, a white vest, and yellow nankeen trousers. His huge shirt-ruffle—or, as the sailors termed it, his head-sail—stuck out a foot at least, while his shirt-frills were fastened by a big diamond. His hat was nicely brushed, and his boots shone as if a dozen darkies had exercised their skill upon them.

He advanced toward us, hat in hand, and, bowing low, exclaimed: "Welcome once more, my glorious old flag and my beloved fellow Union-men. I feel now that I shall receive protection from the laws of my country. I am Mr. Brosnaham, gentlemen, a leading citizen of Pensacola, who for the past year have dwelt beneath the folds of an alien flag and who have been despoiled of my goods and chattels worse than the Egyptians were of old. I welcome you to this loyal city, where I hope the tramp of the rebel hosts will never more be heard, and that we may never again be deprived of that dear flag which has sheltered me from boyhood, and of which I have dreamed every night since it was replaced by that meaningless rag which no one could respect, much less revere. There are a thousand, aye, ten thousand associations—" There is no knowing how long this eloquent gentleman would have continued his patriotic harangue had not the General interrupted the flow of his eloquence by inquiring why the municipal authorities were not present to surrender the city. "Ah!" replied Mr. Brosnaham, "the city is at your feet—a child that has been wronged, asking a mother's protection. When Rome governed the world, it was only necessary to say 'I am a Roman citizen' to insure every consideration. Will not our great Republic—" "Where are the Mayor and City Council?" interrupted the general. "I am truly sorry to say, sir," replied Mr. Brosnaham, "that the fleeing rebels have taken the Mayor's teams into their service to carry their spoils to Mobile, and the City Council, poor fellows, were all pressed into the rebel army, and are now—heaven help them—shouldering a musket under a government they abhor, for they are all, I assure you, sir, devoted to the Union. In the absence, then, of municipal government," continued Mr. Brosnaham, "let me extend to you the liberty of the city and welcome you to our once hospitable but now deserted halls." |

||

—Admiral David Dixon Porter, Incidents and Anecdotes of the Civil War | ||

Union forces constructed makeshift defenses near Lee Square which they called Fort McClellan. However, increased Federal activities along the Mississippi River resulted in the Union force in Pensacola dwindling to fewer than 1,000 by early 1863.[3]

Images[edit]

Confederate troops near Bayou Grande, April 1861

Ninth Mississippi unit, April 1861

Boat-house and landing at Fort Pickens

Casemate battery at Fort Pickens

6th New York Regiment (Wilson's Zouaves) in Fort Pickens

Encampment of 6th New York Regiment (Wilson's Zouaves) outside Fort Pickens

Confederate attack on 6th New York camp during the Battle of Santa Rosa Island

References[edit]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 J. H. Gilman. "With Slemmer in Pensacola Harbor." Battles and Leaders of the Civil War. Century Company, 1887.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Parks, Virginia and Sandra Johnson. Civil War Views of Pensacola. Pensacola: 1993.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 3.7 "Pensacola in the Civil War." Florida Historical Quarterly, Vol. IX, No. 2, 1978.

- ↑ Miller, Francis Trevelyan and Robert Sampson Lanier. The Photographic History of the Civil War. New York: The Review of Reviews Co., 1911.

- ↑ "U.S. Navy and Confederate Shipwreck Project." Florida Division of Historical Resources.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Davis, William Watson. The Civil War and Reconstruction in Florida. New York: Columbia University, 1913.